Memorial Day Remarks and Reflections

Copyright, Terry P. Rizzuti

Estes Valley Memorial Gardens

May 27, 2024, 11:00 A.M.

Welcome to Estes Valley Memorial Gardens. I’m Terry Rizzuti, the Service Officer for American Legion Post 119 here in Estes. This is Raisin, my battle buddy.

First let me say thanks to Bill Smith for inviting me to speak. I hesitated at first, because I thought about the time six years ago when Pat Newsom invited me to speak here. I said Pat, I’d be happy to speak, but I have to give the same speech I gave five years ago because I don’t have the time or energy to write a new one. She said TERRY, nobody will remember what you said five years ago. I laughed and laughed, but then when I got home I wondered if she meant I was unmemorable, or did she mean we’re all so old here in Estes that we can’t remember what we had for breakfast. Anyway, now it’s been eleven years since I first gave this speech, so some of you might have heard this twice already.

Moving on, let me welcome all our guests and thank you all for being here, especially all you veterans facing the more than 200 flag-marked graves behind me.

When I was a little kid, my parents made a point of attending Memorial Day services such as this one. My dad would pile us in the car and take us to St. John’s Cemetery in Rome, NY, where I grew up. St. John’s is located in East Rome, the area of the town that was home to most Italians when I was a kid. All of my deceased relatives were buried there within about 50 yards of each other. It was a very solemn occasion, and I learned from my dad at the time that Memorial Day was a day to think about all our dead relatives, that if it weren’t for them, we might not be here. I didn’t really understand that at age six or seven, and it was several years later before he explained to me other reasons for attending Memorial Day services, reasons having to do with our nation’s heroes.

My dad was a WWII vet, an Army forward observer. I remember growing up looking in his eyes and seeing something different from the other men in his life, including my uncles, his brothers, and I remember when I was about 10 or 11 years old, one of his buddies showed up in a surprise visit, someone who served with him in Italy with the 45th Infantry Division. I remember how they looked at each other, how they hugged, shook hands differently, talked seriously, how they laughed and laughed. And how they cried – I’d never seen my dad cry before.

There was something different about this man, too – this stranger in our home who became an instant friend to us kids – something different in his eyes. I remember how he had that same look as my dad, and I remember thinking that, whatever that look meant, it had to be connected to their war experience. And I remember thinking that I had to know, I absolutely had to know what my dad knew that I didn't. So at a fairly young age I had the sense that I was destined for a military experience.

In fact, when it comes right down to it, my heroes have always been soldiers. One of the very earliest pictures I have of myself was taken when I was about three years old. I’m standing by the Xmas tree in Teddy-Bear pajamas wearing a big grin and proudly holding a toy Thompson Submachine gun.

And I remember hours and hours of playing with toy soldiers, even up into my early teen years. I owned hundreds of toy soldiers and military equipment pieces. Me and my friends would split them up on opposite sides of a room, then shoot rubber bands at them. Whoever had the last man standing won the war. Sometimes a war game would take hours. By the time I was 10 years old, we had taken the game outdoors and were using sling shots with acorns. We lived in the country then, and by age 11, had graduated to BB-guns. That got a lot trickier in terms of safety.

One day in our infinite wisdom we decided we didn’t need toy soldiers anymore, so we started shooting at each other. And one of the kids got hit in the face and started bleeding. He ran home crying to his mother, and pretty soon all the moms got together and took away our BB-guns for the rest of the summer.

This memory now serves for me as a kind of metaphor concerning the escalation effects of war, as well as the wisdom for restricting the use of certain arms:

From rubber bands to BB-guns,

From sticks & stones to bombs & drones.

Wouldn’t it be nice, I mean wouldn’t it be nice if all the moms all over the world got together one day and took away our weapons – even if only for one summer.

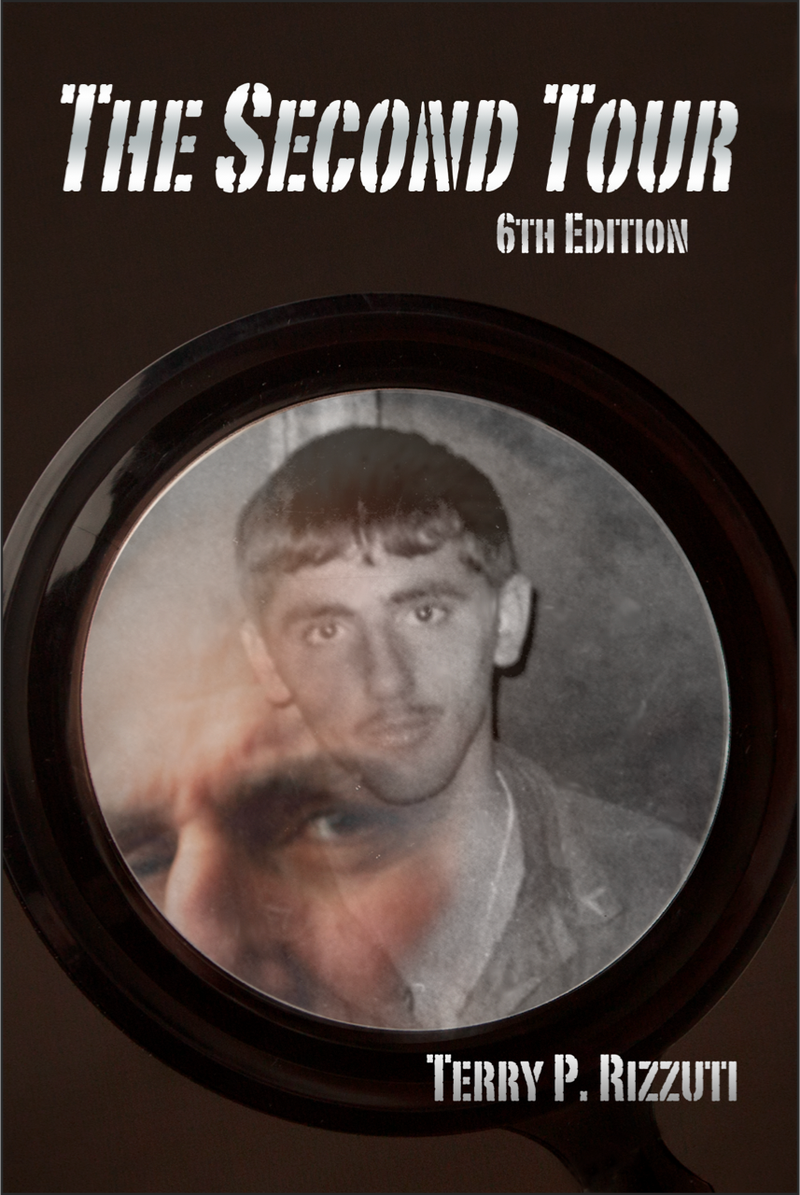

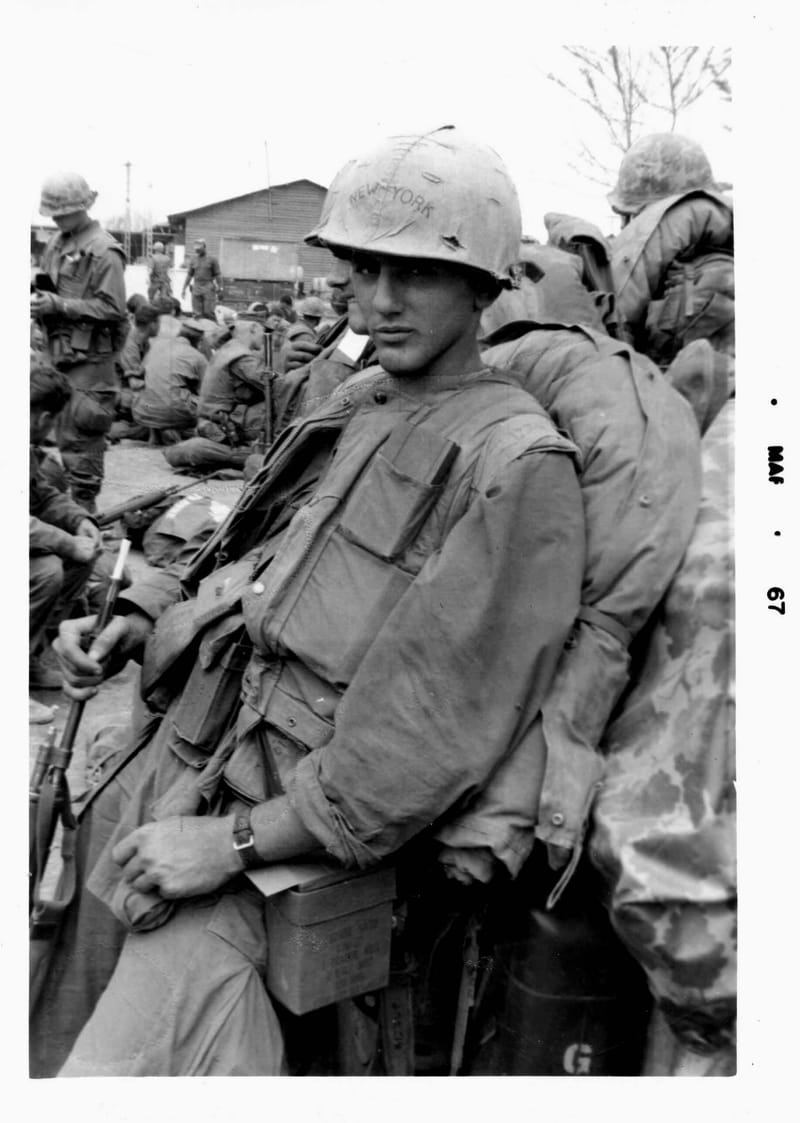

In April 1966, I joined the Marine Corps and was sent to Vietnam in October. Two months later, December 8, 1966, marked the day I knew exactly what my father knew, but I wished to god I didn’t. A year later, in November 1967, I came home, but I came home damaged, not so much from the physical shrapnel wounds I had received, but from mental, emotional and spiritual scars.

I came home angry, angry at myself, angry at the Vietnamese, angry at the military, angry at my peers, angry at god, angry at my father for not telling me the truth about his war experience, and angry at his generation, at my country for sending me to that godawful place to see and do things no twenty-year-old should ever in a million years see or do.

I came home so angry that I couldn't attend functions like this (Memorial services, parades, funerals, or even football games) because I couldn't hold my hand over my heart during the National Anthem or Pledge of Allegiance, couldn't even look at our flag, the flag of the United States, without practically growling at it because it symbolized for me everything that seemed wrong in the world.

But you know what, I’m a little better now – years and years of self-reflection, years and years of mental therapy, and years and years of writing stories about my war experiences have changed all that, have given me new insights, new appreciations, not just for flag and country, but for life itself.

And I owe a lot of my new-found insight to my wife, Mary Banken – God bless her she’s a breath of inspiration, day in and day out, with nothing but a positive outlook on life. I have absolutely no doubt that were it not for Mary I wouldn’t be here speaking today.

But I also owe an ol’ boy in Oklahoma where we used to live. His name was Thom Cook. He’s deceased now. He was a highly decorated, two-tour Army special forces Vietnam Vet, a medic who served with the 173rd Airborne. He was Commander of one of our local VFW’s, and before that, he was the Veterans Service Officer. He chose me as his unofficial assistant and called me the Mafia Marine.

One day during an official Post meeting, Thom noticed I wasn’t putting my hand over my heart during the Pledge of Allegiance, that I wasn’t saying the words, and he demanded to know why, so I told him, right in front of all the other officers and general membership. He listened to the anger in my voice, and even though he understood exactly where I was coming from, he said “Mafia Marine (he had one of those really deep gravelly voices), Mafia Marine, you need to put the flag out – every day,” and then he changed the subject. It was almost like it was an order: “Put the flag out, Marine.”

This was in 1998 or 9, and for a couple of years that statement weighed on me. And then Sept 11th, 2001, changed the world for me. We used to have a saying in Vietnam whenever we’d get disgusted with the situation there. We used to say, it’d be different if they were coming across our own backyards. Well, they came in our front door that day, so I started putting a flag out in the morning, and taking it in at night. And over time, I started to notice a slight hesitation each time I did so, a slight pause. It started with me thanking Thom, and eventually grew to me thanking the creator. And now it’s become a brief prayer of gratitude for this great nation of ours, this nation we call the United States of America.

But let me stop here and shift gears, because you know what? Today isn't about me, or even people, veterans, like me. It's about our dead, our dead heroes. It's about the more than one million men and women (more than 6,000 of whom were Coloradans) whose lives were taken too soon, about those who died serving this country before they had a chance to be damaged, before they had the luxury of living to my age, before they had received the gift of truly experiencing this great country of ours, flawed as it may be, and it is flawed, and before they had a chance to hold their children and their grandchildren, a chance to rock them in their laps, to hear them laugh, cry or giggle, a chance to live their lives as we do.

Today is about people, heroes, like Lance Corporal Richard Wayne McVay of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who was wounded-in-action on Dec 8, 1966, and died the next day.

It’s about Private First-Class Marion E. Patrick, of Rossville, Georgia, who was killed-in-action on May 2, 1967.

It’s about Lance Corporal Charles W. Bricker, of Rushville, Illinois, who was also killed-in-action on May 2, 1967.

It’s about Private First-Class Percy E. Watson, of Selma, North Carolina, who was wounded-in-action on May 2, 1967, and died a week later.

It’s about Lance Corporal Raymond Martin Sieger, of Chicago, Illinois, who was killed-in-action on May 25, 1967.

These five men, all close friends of mine, were so severely wounded, they came home in closed caskets. Bricker was turned into hamburger meat by a boobytrap, so too were Patrick and Watson. McVay was shot in the face, his lower jaw completely blown off. Sieger was decapitated by an RPG.

So for me, today is also about the families and friends of those of our heroes who returned in closed caskets, because for them (the families and friends), there’s a deep, deep-seated sense of loss and pain that comes not just from a life-lasting final memory of watching flag-draped wooden boxes lowered into marked graves, but also wondering, questioning whether their loved ones are truly inside those caskets, whether their government, their military, was pulling a fast one on them.

So, by way of example, earlier I mentioned the death of Lance Corporal Charles W. Bricker, who was killed-in-action on May 2, 1967. Nearly 42 years later, in January 2009, I was contacted by his sister, Linda Sample. Linda begged me for the true story of why her brother’s casket was closed.

A year later, I was contacted by the parents of Bricker’s best friend, people who thought of Bricker as a nephew. They too wanted answers to that question. And the answers were difficult to give because Bricker had been so severely wounded when last I saw him. Recalling that image and describing it to his sister and his friends led to a river of tears and flood of guilt.

Forty-five years later, in December 2011, on the eve of the anniversary of Richard Wayne McVay’s death, I was contacted by Joan Tomich, his high school girlfriend. Joan also begged me for the details regarding the closed casket. Again, this was not an easy story to share, because McVay’s face had been obliterated. But she insisted on knowing the details. She wanted to know if what I wrote in my book was true. I said Yes, and she thanked me for writing it, said it allowed her to walk beside Richard on his last day on earth.

But, the really unexplainable thing to me is that Joan, a married woman with children, who lives in Arizona, joins McVay’s twin brother Robert and has visited his grave in Pittsburgh every single year since 1967. Can any of us here imagine, let alone fully understand, what it must feel like for Joan’s family (her husband and kids), knowing she’s still in love with a ghost that’s been dead for more than 57 years.

By way of another example, I mentioned the death of Private-First-Class Percy Watson, who was also killed-in-action on May 2, 1967. Just last Fall (September 2023), nearly 57 years after his death, I was contacted by his family and friends wanting to know the true story of why Watson’s casket was closed.

Summing it up, for me at least, but hopefully for you too, today is a day to focus on the fact that there are people in our country that evidence the greatest altruism, men and women who give all that can be given – their very lives – and those who give their sons, their daughters, their sisters and brothers, to the government when it issues the call.

And you know what? I can’t remember who said it, maybe Jim Webb, perhaps John McCain – “Honor can’t be found in choosing your battles; it’s found in answering the call.” He was talking about us Vietnam War veterans, about the fact that in spite of a war’s controversy, all men and women who serve our country deserve our respect, our admiration.

These men and women we honor today – they not only answered the call, they paid the ultimate price. So we gather here today to not only respect that altruism, but also that sense of honor, and pass that understanding down to our children and their children, the way our parents passed it down to us. We gather here today to cherish that honor and altruism, to salute it and salute them, our heroes.

So I ask you to join me in a brief salute, a salute to our flag as one of the symbols of all of our fallen men and women. And I ask that as you do so, to simultaneously whisper a short prayer to yourself, a simple, brief thank you for their sacrifice, and a thank you for the sacrifice of their families and friends.

And now I thank you all for being here and listening, and I ask that you now please join me in a salute to the flag of our United States of America. Thank you.